Allergic urticaria

The child is prescribed a hypoallergenic diet according to A.D.

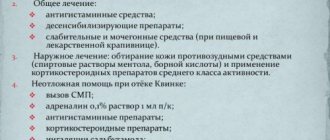

Ado. Food allergens to which the body reacts and histamine-releasing products should be excluded from the diet. The medications prescribed depend on how severe the child's hives are. In case of exacerbation of severe urticaria, take some of the following medications (as prescribed by a doctor):

- clemastine

— chloropyramine 2.5% (course 5-7 days)

- systemic glucocorticosteroids (if the above drugs were ineffective): dexamethasone, prednisolone

- according to indications, hemodez 200-400 ml intravenously, 3-4 injections

- fexofenadine (Telfast)

- loratadine (Claritin) once a day

- ketotifen

For the treatment of exacerbations of moderate urticaria, take:

— clemastine (tavegil) 0.1%

— chloropyramine (suprastin) 2.5%

— systemic glucocorticosteroids (according to indications)

- fexofenadine

- loratadine

- ketotifen (zaditen) 0.001 g 2 times a day

In case of mild exacerbations of urticaria, elimination measures are carried out. Glucocorticosteroids are not used. Then fexofenadine (Telfast) and loratadine are used once a day. Course – 1 month. Ketotifen is taken for a course of 3 months.

Treatment in a hospital is 18-20 days. If necessary, SIT and a course of histaglobulin are carried out in an allergy hospital or office.

Chronic recurrent urticaria: syndrome or disease?

Urticaria is characterized by the appearance of an itchy, erythematous rash, the elements of which rise above the surface of the skin. The primary element in urticaria is the blister (urtica). It turns pale when pressed, which indicates the presence of dilated blood vessels and swelling in the skin lesions. Microscopic examination in patients with urticaria reveals expansion of small venules and capillaries, affecting the superficial layers of the skin, and to a lesser extent, its papillary layer, as well as swelling of collagen fibers. More severe inflammation, in which similar changes develop in the deep layers of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, leads to the development of Quincke's edema (angioedema). Hives can appear on any part of the skin, while angioedema most often occurs in the face, tongue, limbs and genitals. Urticarial rash is accompanied by itching, which intensifies at night and persists for a few minutes to 48 hours [1]. After a specified period, the elements of the rash disappear without a trace, however, new rashes may appear at different times in other parts of the body [2,3]. According to the course, acute (up to 6 weeks) or chronic (more than 6 weeks) urticaria is distinguished. When a urticarial rash appears repeatedly, recurrent urticaria is diagnosed. The prevalence of urticaria in children is about 2–3%, with at least one episode of urticaria occurring in 15–20% of both pediatric and adult populations during their lifetime [4,5]. There are many classifications of chronic urticaria, which take into account both the clinical manifestations of the disease and its etiology, but taking into account the pathogenesis of the disease is the most appropriate for choosing therapy (Table 1) [1]. Thus, urticaria as a nosological form can only be designated as its idiopathic type and associated with exposure to physical factors; in all other cases it is only a syndrome, the causes of which are different. Most often, urticaria occurs with: • allergic and non-allergic reactions to medications, food and food additives, inhaled allergens (pollen, molds, house dust); • intravenous administration of blood products and blood substitutes; • infections: bacterial, fungal, viral and parasitic; • insect bites and stings • systemic connective tissue diseases • serum sickness • malignant neoplasms accompanied by acquired deficiency of C1 and C1-complement inactivator. Acute urticaria in children is most often associated with food, drug, insect allergies, as well as viral infections. Moreover, in half of the patients the cause of the urticarial rash cannot be identified - such urticaria is designated as idiopathic. With chronic urticaria, only 20–30% of children can identify its cause, which is most often represented by physical factors, infections, food allergies, food additives, inhaled allergens and medications. However, one should not limit oneself to the differential diagnosis of allergic, infectious and physical causes of urticaria, as is usually done in the practice of a pediatrician and allergist. In all cases of chronic urticaria, it is necessary to exclude a wide range of diseases [6]. Urticarial rash, which occurs when exposed to physical factors, is the most common type of chronic urticaria [7]. In physical urticaria, an itchy urticarial rash appears immediately after exposure to the corresponding provoking factor and usually persists for no more than a few hours. An exception is urticaria due to a delayed reaction to pressure, in which the rash appears 2–6 hours after pressure and persists for more than a day. Unlike other types of physical urticaria, delayed pressure urticaria does not respond well to antihistamines (histamine H1 receptor antagonists); when it is severe, it is often necessary to prescribe large doses of systemic glucocorticosteroids [8]. The most common causes of physical urticaria are pressure (in addition to delayed pressure urticaria, pediatricians often have to deal with dermographic urticaria, urticarial dermographism, where friction causes a rash); overheating or physical exertion (causes cholinergic urticaria); sunlight (solar urticaria), cold (cold urticaria) and water (aquagenic urticaria) [9,10]. Another common type of urticaria is contact urticaria. It can be allergic or non-allergic (other terms - pseudo-allergic, reactive-toxic). Non-allergic “provocateurs” of urticaria rash in contact urticaria are widespread in the environment. These include various chemical components of food products, cosmetics, household chemicals and medications. Allergic contact urticaria, as a manifestation of an IgE-mediated allergic reaction, is most often observed in children with allergic diseases and, as a rule, the main mediator causing inflammation is histamine. Most often, such a rash occurs upon contact with detergents, latex, fresh fruits, berries and vegetables in patients with hay fever. With this type of urticaria, the main thing is to identify the causative allergen and eliminate it. Topical corticosteroids and antihistamines are used as first-line treatment [11]. The role of infectious diseases, especially parasitic infestations, in the occurrence of urticaria has not been fully established. Most researchers indicate that the frequency of infections, both bacterial, viral, fungal, and parasitic, in patients with urticaria does not differ from that in the general population, however, there is an opposite point of view, according to which invasion of the gastrointestinal tract by parasites is considered an important cause hives. The vast majority of available publications do not meet the criteria of evidence-based medicine, so from this point of view their reliability cannot be assessed. Single reports, as well as those that are not sufficiently consistent with the rules of evidence-based medicine, concern chronic urticaria in children and adults associated with infection with Epstein-Barr viruses, influenza, parainfluenza and cytomegalovirus. Analysis of rare descriptions of cases of chronic urticaria associated with various bacterial and fungal infections does not allow us to accurately determine whether the urticarial rash is associated with microorganisms, or whether it is an adverse reaction to treatment with antibacterial and antifungal drugs [12]. Helicobacter pylori infection has also been implicated in chronic urticaria. It has been established that the frequency of its detection among patients with urticaria and in the population is the same. However, the immune response to H. pylori may differ in patients with urticaria. It was revealed that in patients with chronic urticaria infected with H. pylori, the production of immunoglobulin G, as well as immunoglobulin An, specific to the lpp20 lipoprotein, is more pronounced than in infected patients without urticaria. This lipoprotein is associated with H. pylori and can be considered as one of the markers of this infection. Moreover, an analysis of existing studies revealed that remission of urticaria is more likely in cases where antibacterial therapy leads to eradication of H. pylori. The authors of these studies conclude that testing for H. pylori is appropriate after ruling out other most likely causes of urticaria; if an infection is detected, prescribe appropriate treatment and ensure eradication of the pathogen [13]. Group A streptococci are also considered as a possible factor playing a role in the occurrence of urticaria. In chronic urticaria, antibodies to these microorganisms are often detected, and the effect of treatment with erythromycin, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime is noted. However, these data also concern very small groups of patients and cannot be considered evidence of the role of streptococci in the development of urticarial rash [12]. A significant number of parasitic infestations, including Ascaris, Ancylostoma, Strongyloides, Filaria, Echinococcus, Schistosoma, Trichinella, Toxocara, Fasciola, are associated with urticaria. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions, such as urticaria and angioedema, occur during the migratory phase of parasite development. These parasitic infections are usually accompanied by severe eosinophilia, so they should not be included in the differential diagnosis plan if the patient does not have a corresponding clinical picture and an increased number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood. Regarding the role of protozoa in the development of urticaria, most researchers discuss giardiasis, but there is no consensus on the role of Giardia in urticaria. Some authors consider the appearance of urticarial rash in giardiasis to be a rare phenomenon [14], others are convinced of the undoubted existence of such an association [15]. Moreover, it is believed that the manifestations of food and drug allergies can intensify during the period of manifestation of parasitosis, which significantly complicates the differential diagnosis and leads to a chronic course of urticaria [16]. Rare types of chronic urticaria include urticarial vasculitis, hereditary angioedema, and mastocytosis. It should be emphasized that urticarial rashes that persist longer than 24 hours and, especially, leave behind pigmentation, may be based on an immune complex nature. This indicates the need to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is a characteristic sign of an autoimmune disease, primarily systemic lupus erythematosus [1]. Hereditary angioedema is a rare autosomal dominant disease, which is based on a deficiency of the complement component C1 inhibitor. The disease is manifested by recurrent edema, the distinctive characteristic of which is the absence of itching. The term "mastocytosis" unites a heterogeneous group of diseases, the basis of which is the abnormal growth and accumulation of mast cells. Urticaria in mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa) can be part of the symptom complex of systemic mastocytosis, which affects various organs, or be an independent disease (in these cases they talk about the cutaneous form of mastocytosis) [17]. These rare types of chronic urticaria are the most resistant to treatment. Antihistamines for such urticarial rashes give an inconsistent and, as a rule, insufficient effect. This can be explained by the fact that not only histamine, but also other mediators, as well as cellular immune reactions and those mediated by the complement system, are involved in the development of inflammation in urticaria, which accompanies systemic diseases. If the cause of chronic urticaria cannot be determined during the examination, a diagnosis is made: “chronic idiopathic urticaria” (CIU). With CIC, urticarial elements persist longer than with various types of physical urticaria - usually up to 8-12 hours and are accompanied by more severe itching, especially in the evening and at night. Half of the patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria are accompanied by Quincke's edema [8]. With CIC, 25–45% of patients show signs of an autoimmune disease - histamine-releasing IgG antibodies against the high-affinity receptor for IgE (FcεRI) or against IgE itself [18]. In patients who have such antibodies, compared to those who do not have them, the level of serum IgE is significantly lower, and a profuse and widespread urticarial rash is characterized by severe itching [19]. When examining skin biopsies in patients with CIC and the presence of FcεRI/IgE antibodies, perivascular infiltrates are often detected, mainly consisting of neutrophils, eosinophils and mononuclear cells [20]. Almost a third of patients with CIC have autoimmune reactions to thyroid tissue. However, most of them do not have any clinical symptoms of damage to the thyroid gland and changes in the levels of thyroid hormones; there is a decrease or disappearance of urticaria symptoms after the administration of levothyroxine [18,21,22]. In addition to assessing the history, clinical symptoms of the disease and its course, the following laboratory tests help in the differential diagnosis of chronic urticaria: • Skin tests or determination of specific IgE antibodies in the blood. They help to identify a “causally significant” allergen in cases where anamnestic data allows one to suspect a connection between the rash and food, medications, insect bites, plant pollen, or animals. Negative results of these tests exclude the atopic component of urticaria. • Culture (usually from the throat or other site of inflammation) to isolate a culture of bacteria and determine their sensitivity to medications. Used if inflammation is suspected or present, or if the patient has a history of fever or sore throat. • Thyroid function tests, including antithyroid microsomal antibodies and antithyroglobulin antibodies. These tests should be used first if the patient's immediate family has thyroid disease (usually in the female line) or symptoms indicating decreased thyroid function. However, in the presence of autoantibodies to the thyroid gland, its function is often not impaired. • Determination of the concentration of C1-esterase inhibitor, the level of C3 and C4 complement components. These tests should be used if the child's relatives have had cases of angioedema or an exacerbation of urticaria was accompanied by difficulty swallowing, breathing, or angioedema. • Stool analysis to detect helminth eggs or parasites. Particular attention should be paid to this study if there is a history of eating undercooked/done meat or living in conditions of unsatisfactory sanitary conditions. • Tests for the presence of autoantibodies: antinuclear antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, anti-FcεR1α antibodies. It is especially important to conduct these studies if the patient has arthritis, photosensitivity, or other symptoms that indicate the likelihood of a systemic connective tissue disease. The presence of a positive reaction in the form of wheal formation and hyperemia when performing a skin test with the patient’s own blood serum suggests the presence of autoantibodies to FcεRI/IgE [23]. • Analysis of blood cells, ESR, C-reactive protein level. It is an obligatory component of the examination and allows to exclude diseases accompanied by inflammation, including systemic vasculitis. • Determination of the level of cold agglutinins and cryoglobulins in the blood in children with cold urticaria. Detection of cryoglobulin requires further exclusion of chronic hepatitis or malignancy. • Identifying and treating H. pylori infection helps some people get rid of hives. Additional investigations: • The presence of urticaria caused by physical factors can be confirmed using appropriate provocative tests: heat, pressure, cold, sunlight, water, exercise, vibration. • Tolerance to foods, including those to which sensitization has been identified using skin tests or determination of specific IgE in the blood, should be checked with a trial diet. The suspected product and its contents are excluded for several days, after which the product is reintroduced into the diet. The method of elimination-provocative diet is set out in the relevant manuals. You should be aware of urticaria, which occurs only when a food challenge (for example, eating seafood) and physical activity are combined. Practical advice: • If a young child has chronic urticaria, systemic diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, serum sickness syndrome, latent infection, malignant neoplasm) should first be excluded. Similarly, in older children, if, in addition to urticaria, any nonspecific symptoms (especially progressive ones) are detected. • If the urticaria rash persists for more than 24 hours, urticarial vasculitis should be excluded. In these cases, microscopic examination of a skin biopsy is indicated. • If the patient's condition is not impaired and the rash appears and disappears (or migrates) in less than 24 hours, it is advisable to first rule out: – urinary tract infection, especially caused by Escherichia coli; – upper respiratory tract infection caused by streptococci; – Chlamydia pneumoniae infection; – H. pylori infection; – herpes viral infection caused by cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes virus type 6; - parasitic invasion (especially if the child lives in adverse sanitary -epidemiological conditions or recently went to other regions); - autoimmune diseases (autoimmune diseases of the thyroid gland, celiac disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, systemic juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory intestinal diseases). • In the absence of the symptoms that are concomitant, the effects of physical factors as the cause of urticaria (sunlight, cold, overheating, water, vibration, pressure, etc.) should be excluded first of all. • Carry out the treatment of diseases available or detected during the survey. If the urticaria is preserved and all possible reasons are excluded, to recognize it idiopathic, to prescribe treatment. In case of doubt, conduct an investigation. The main medical treatment of urticaria (both acute and chronic) is antihistamines. Despite the fact that the first -generation antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, etc.) effectively eliminate the symptoms of urticaria, their prescription is associated with the occurrence of a large number of side effects. These include drowsiness, anticholinergic effect (dry mucous membranes, dizziness, constipation, urination, etc.), memory impairment, attention that can be preserved within a day after taking the drug. In accordance with the International Nettle Management Guide (EAACI/GA2len/EDF/Wao Management Guideline), first -generation antihistamines (sedative) should not be used as a priority treatment of patients with urticaria. An exception may be only those situations in which it is impossible to use 2 generation antihistamines. Currently, the appointment of unnoticed antihistamines of 2 generations is considered priority. These drugs, devoid of side effects inherent in antihistamines of the 1st generation, no less effectively block N1 -receptors to histamine and suppress the symptoms of urticaria, significantly improving the quality of life of patients [24,25]. Among the universal antihistamines, Disloratadin (Erius), which is the primary pharmacologically active metabolite of a well -known Loratadin, deserves special attention. Desloratadin is a selective antagonist H1 - receptors. It has special pharmacokinetic properties: rapid absorption, neither food and its character or drinking juices do not affect its bioavailability. The half -life of Erius is 21–27 hours, which allows you to maintain its real therapeutic activity of unchanged with a single intake per day (unlike other second -generation antihistamines). Moreover, the study of the compatibility of desloratadine with other drugs did not reveal any significant interactions. The security profile of Erius is comparable to the use of placebo, which was established in a controlled clinical examination with the participation of about 2000 patients who received the drug at a dose of 5 mg daily [26]. During laboratory studies, it was found that desloratadine has a pronounced ability to contact H1 - receptors to histamine; Its activity in blocking these receptors exceeds that all existing antihistamines existing today. A distinctive feature of Erius from other second -generation anti -allergic drugs is the triple mechanism of action: desloratadin not only blocks H1 - hystamine receptors, but also has pronounced anti -allergic and anti -inflammatory activity by inhibiting the synthesis of many other mediators with fat cells, basophils and other cells participating in the development of inflammation [ 27]. These pro -inflammatory mediators include leukotrien C4, prostaglandin D2, triptase, Rantes, induced by a factor in tumor -alpha necrosis, p - sealectin, an intercellular adhesion -1 molecule, which activates histamine (IL - 1β, IL - 4 , IL - 5, IL - 6, IL - 8, IL --13, IL --18) and the factor of platelet activation. These inflammation mediators play a role in any allergic and pseudo -allergic reactions, therefore, non -loratadin has an anti -inflammatory effect with various manifestations of both respiratory and skin allergies and their clinical analogues of pseudo -allergic genesis. The effectiveness of Erius in suppressing inflammation in the skin is also partially explained by the suppression of keratinocytic activation, in particular - inhibition of the ability of gamma -interferon to cause the ICAM -1 expression, leukocyte antigen -DR (HLA - DR) and the activation of the main histocompatibility complex of class I, as well as the release of Rantes INETLIKINA - 18 [28]. Thus, Erius inhibits the development of not only the early, but also the late phase of an allergic reaction, which is associated with the accumulation of "inflammation cells" in the lesion. This unique pharmacological effect of desloratadine inhibits the formation of chronic inflammation, which, in the absence of adequate therapy, can lead to a prolonged course of the disease. Additional confirmation of the anti -inflammatory activity of desloratadine, associated with the suppression of not only allergic inflammation, is its ability to inhibit the development of erythema when exposed to ultraviolet radiation of the B - aPASON [29]. The clinical efficiency and safety of desloratadine under HIK was proved during multi -centered randomized placebo -controlled studies using a double blind method. The effectiveness of Erius regarding the suppression of itching was noted from the first day of the drug and remained within the next 6 weeks of the study. In addition to itching, the use of desloratadine led to the elimination/significant decrease in the severity of such symptoms of HIK as sleep disturbance, a decrease in the activity and performance of the patient. At the same time, side effects were absent [30]. Thus, the use of Erius in chronic urticaria is accompanied by a significant improvement in the quality of life of patients. Effective suppression of the symptoms of urticaria occurs already on the first day of treatment, the entire period of use of the drug continues and consists in a quick and persistent decrease in the rash, itching, improving sleep and the activity of patients in the daytime. Among other drugs for the treatment of chronic urticaria, it should be noted by N2 -receptors blockers to histamine. They are not used as standard treatment, however, their combined use with H1 antagonists in some patients significantly increases the effectiveness of treatment [8]. The treatment of patients with chronic urticaria glucocorticosteroids is also not a standard therapy method, since its effectiveness is ambiguous. This treatment is believed to give a result and is shown if the patient has an autoantiber to FcεRI/Ige, as well as with severe urticaria. In this contingent of patients, the effect of the use of cyclosporine [31] and intravenous administration of immunoglobulins is possible [32].

References 1. Ring J, Brockow K, Ollert M, Engst R. Antihistaminesinurticaria. ClinExpAllergy 1999;29(Suppl. 1):31–37. 2. Simons FER Prevention of acute urticaria in young children with atopic dermatitis. J of Allergy and Clin Immunology 2001;107(4):703–706. 3. Warin RP, Champion RH: Urticaria, London, 1974, WB Saunders. 4. Gervazieva V.B., Petrova T.I. Ecology and allergic diseases in children. Allergology and Immunology 2000;1(1):101–108. 5. Allergic diseases in children. Guide for doctors. Ed. M.Ya. Studenikina, I.I. Balabolkina. M., Medicine, 1998.–347 p. 6. Novembre E, Cianferoni A, Mori F, et al. Urticaria and urticaria related skin condition/disease in children. Eur Ann Allergy ClinImmunol 2008:40:5–13. 7. Barlow RJ, Warburton F, Watson K, Black AK, Greaves MW. Diagnosis and incidence of delayed pressure urticaria in patients with chronic urticaria.J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;29: 954–958. 8. Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy ClinImmunol 2000;105:664–672. 9. Monfrecola G, Masturzo E, Riccardo AM, Balato F, Ayala F, Di Costanzo MP. Solar urticaria: a report on 57 cases. Am J Contact Dermatol 2000;11:89–94. 10. Luong KV, Nguyen LT. Aquagenic urticaria: report of a case and review of the literature. AnnAllergyAsthmaImmunol 1998;80:483–485. 11. Wakelin SH. Contact urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001;26:132–136. 12. Chronic urticaria and infection. Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2004, 4:387–396. 13. Wustlich S, Brehler R, Luger TA, et al. Helicobacter pylori as a Possible Bacterial Focus of Chronic Urticaria. Dermatology 1999;198:130–132. 14. Hill DR, Nash TE: Intestinal flagellate and ciliate infections. In Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF (eds): Tropical Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone, 1999, pp. 703–719. 15. Dermatoses and parasitic diseases in children and adolescents. Practical guide. Ekaterinburg: Ural University Publishing House, 2006, 61 p. 16. IA Khan, MA Khan. Urticaria and Enteric Parasitosis: an agonizing condition. Med. Channel, 1999; 5(4):25–28. 17. Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L et al. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res 2001;25:603–625. 18. Ryhal B, Demera RS, Choenfeld Y, Peter JB, Gershwin ME. Are autoantibodies present in patients with subacute and chronic urticaria? J Invest ClinImmunol 2001;11:16–20. 19. Sabroe RA, Seed PT, Francis DM, Barr RM, Black AK, Greaves MW. Chronic idiopathic urticaria: comparison of the clinical features of patients with and without anti–FeRI or anti–IgE autoantibodies. J Am AcadDermatol 1999;40:443–450. 20. Grattan C, Boon AP, Eady RA, Winkelmann RK. The pathology of the autologous serum skin test response in chronic urticaria resembles IgE–mediated late–phase reactions. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol 1990;93:198–204. 21. Gaig P, Garcia–Ortega P, Enrique E, Richart C. Successful treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria associated with thyroid autoimmunity. J Invest Allergol Clin Immunol 2000;10:342–345. 22. Zauli D, Deleonarid G, Goderaro S et al. Thyroid autoimmunity in chronic urticaria. Allergy Asthma Proc 2001;22:93–95. 23. Sabroe RA, Grattan CE, Francis DM, Barr RM, Kobza Black A, Greaves MW. The autologous serum skin test: a screening test for autoantibodies in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 1999;140:446–452. 24. Zuberbier T, Greaves MW, Juhlin L, Mark H, Stingl G, Henz BM. Management of urticaria: a consensus report. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc 2001;6:128–131. 25. [Guideline] Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev–Jensen C, Walter Canonica G, Church MK, Gimenez–Arnau AM, et al. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy.Oct 2009;64(10):1427–43. 26. Geha RS, Meltzer EO. Desloratadine: a new, nonsedating, oral antihistamine. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;107:751–762. 27. Bachert C. Therapeutic points of intervention and clinical implications: role of desloratadine. ClinExpImmunol 2002. 28. Munster I, Pleyl-Wisgiki G, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Ring J, Behrendt H. Desloratadine regulates the expression of MHC-class molecules and costimulatory signals in cultured human keratinocytes. Allergy 2002;57(Suppl. 73):307–308. 29. Reuther T, Williams SC, Kerscher M. Anti-inflammatory activity of desloratadine: a pilot study. Poster abstract presented at the 20th World Congress of Dermatology, 4–5 July 2002, Paris, France. 30. Ring J, Hein R, Gauger A, Bronsky E, Miller B. Once-daily desloratadine improves the signs and symptoms of chronic idiopathic urticaria: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:72–76. 31. Grattan C, O'Donnell BF, Francis DM et al. Randomized double–blind study of cyclosporin in chronic 'idiopathic' urticaria. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:365–372. 32. O'Donnell BF, Barr RM, Black AK et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol 1998;138:101–106.

Idiopathic urticaria

To treat this type of urticaria, the child must follow a hypoallergenic diet according to A.D. Ado. The same medications are recommended as for the treatment of exacerbations of moderate urticaria. In case of torpidity, the child may be prescribed long-acting glucocorticosteroids for a course of 2-3 weeks to symptomatic therapy.

Detoxification therapy involves the administration of hemodez 400 mg and the intake of sorbents. The child is prescribed digestive enzymes, for example, mezim or festal, but not in all cases. Based on the identified pathology, the child is prescribed symptomatic treatment: antifungal, antibacterial, etc.

If treatment with antihistamines is effective, then a course of histaglobulin follows.

Other reactions to the allergen

With allergic urticaria (which is much less common, and it is possible to identify a specific allergen), upon repeated contact with the allergen, angioedema may occur - allergic swelling of the skin or mucous membranes in response to exposure to the allergen.

Angioedema (usually the lips, tongue, eyelids, skin of other parts of the body) occurs at the site of contact with the allergen. Most often in response to food allergens or insect bites, less often - to other allergens. It may be accompanied by itching, redness of the skin, burning sensation, etc. It may be accompanied by other manifestations of allergies (hives, runny nose, sneezing, watery eyes).

Angioedema is an unpleasant condition, but is not always life-threatening. Treatment for angioedema is oral antihistamines and elimination of contact with the allergen.

A dangerous situation is angioedema, which spreads to the upper respiratory tract.

This leads to breathing problems (which is accompanied by suffocation, difficulty speaking and breathing, hoarseness, change in complexion) and may be accompanied by an anaphylactic reaction (anaphylactic shock, drop in blood pressure, dizziness, impaired consciousness, etc.).

Symptoms of anaphylaxis develop within a few minutes to hours after contact with the allergen.

First aid:

- Call an ambulance! It is important not to waste a minute, every second is important to provide medical care! The first aid remedy in such a situation is adrenaline (in our country it is administered by a doctor)

- Eliminate the allergen if possible (remove the insect sting, stop the supply of medicine, food product, etc.)

- Provide plenty of fluids.

- Take the child to the hospital.

Antihistamines and hormonal drugs have a delayed effect, preventing the development of anaphylaxis in the future, but act more slowly than adrenaline for anaphylaxis that has already developed

At risk are children with: anaphylactic reactions, atopy or allergic reactions in the past/in the family (including bronchial asthma, drug allergies, etc.)

Prevention:

- avoid contact with allergens; if such contact is necessary, then do it only in a place where there is an anti-shock first aid kit

- destroy insects on the site (wasps, hornets)

- consult an allergist to identify the allergen

- wear bracelets with information about personal allergens

- Those who have had anaphylactic reactions in the past can carry at least two epinephrine auto-injectors (Epipen, Jext, Adrenaclick) with them.

Thus, if your child has symptoms of urticaria, then in any case, you should contact your pediatrician. It is best to take further actions under the supervision of a doctor.

Temperature urticaria

As with the types of urticaria described above, the child follows a diet according to A.D. Ado. You should adhere to a gentle thermal regime, avoiding high and too low temperatures. If the effect of thermal factors on the body is inevitable, antihistamines should be taken before contact. In cases of photodermatosis, photosensitizing drugs are discontinued.

For the generalized form, take clemastine 0.1% 2 ml, chloropyramine (suprastin) 2.5%, dexamethasone, prednisone. For mild to moderate cases, take fexofenadine and loratadine once a day. Doctors may also prescribe antihistamines with a stabilizing effect on mast cell membranes.