06/07/2018 I’ll start today’s article with what has already become a classic situation.

A person comes to see a doctor (dermatologist or oncologist) and shows him his moles.

And then something like this happens:

– You have dysplastic nevi here, here and here.

- What is this? Is it dangerous?!

– Dysplastic nevi are moles with an uneven edge and uneven color. Dysplastic nevi can develop into melanoma and must be removed.

- Oh!!! How scary!!! Let's delete it quickly!!!

The moles are safely removed and sent for histology.

A person comes home and starts reading on the Internet about dysplastic nevi. And then they add fuel to the fire:

- A dysplastic nevus is any nevus with an uneven edge and uneven coloration.

- All dysplastic nevi turn into melanoma in 146% of cases.

- To prevent death from melanoma, you need!!! URGENTLY!!! remove all dysplastic nevi.

All this “beauty” has been copied from one site to another for many years and fills the domestic segment of the Internet to the brim.

Let's understand all this from the point of view of evidence-based medicine.

How dangerous are dysplastic nevi?

There are specific, proven figures here that it would be better for those who spread hysteria on the “Internet” to become familiar with.

- The annual risk of a dysplastic nevus turning into melanoma is 1 in 10,000. According to the authors [4], this is very low.

- About 70% of melanomas develop not against the background of nevi, but against the background of unchanged skin [5].

- A study examining the genetic profile of atypical nevi has challenged the hypothesis that they are precursors to melanoma [6].

- In two studies, the authors followed patients with incompletely removed, histologically confirmed dysplastic nevi for a long time (up to 17 years) [8,9]. Based on this, the very thesis about the increased risk of developing melanoma from a dysplastic nevus can be seriously questioned.

Melanocytic nevi

The article presents options, clinical manifestations, clinical features, and diagnostic criteria for various types of melanocytic nevi.

The increased attention of doctors of all specialties to melanocytic nevi (MN) is explained by late diagnosis and poor prognosis of melanoma developing against them - one of the most malignant human tumors. Making up less than 10% of the structure of malignant skin neoplasms (MSN), melanoma is responsible for 80% of deaths in the entire group of MNS /1/. On the other hand, timely treatment of melanoma (at the stage of “horizontal” growth) allows patients to achieve a 10-year disease-free period of life in 90% of cases /7/.

It is known that melanoma occurs in approximately 50% of cases against the background of MN, which may be due to a common genetic defect - loss of heterozygosity in the 9p21 locus of chromosome /16/ with a mutation in the nRAS oncogene /20/ in both melanoma tissue and MN, against the background which it developed.

The most important factor in the development of melanoma against the background of MN is exposure of human skin to an excessive dose of UVR, which leads not only to damage to keratinocytes and melanocytes, but also to immunosuppression, caused primarily by the suppression of NK cells. In addition, risk factors for the development of melanoma are: skin phenotype I-II (proneness to sunburn of the skin, red hair, blue eyes, fair skin), 3 or more episodes of sunburn of the skin during life, the presence of freckles and lentigo or 3 or more atypical MN, familial cases of melanoma in close relatives /1/.

MNs are observed in ¾ of Caucasians /18/ and are benign tumors of the melanogenic system. Only some of them transform into melanoma (melanoma-dangerous MN) or are a marker of an increased risk of its development. /4,11,12,19/. Identifying them in order to prevent the development of melanoma is extremely important for doctors of all specialties.

The vast majority of MNs are acquired. They are divided into regular and special types.

Among common MNs, borderline, complex (epidermal-dermal) and intradermal forms are distinguished /15)/. They arise after the birth of a child and have characteristic dynamics: first, due to the proliferation of nevus cells along the border of the epidermis and dermis, the formation of borderline MN occurs; over time, nevus cells move into the dermis, forming mixed MN; the borderline component may disappear with age, leaving only the dermal (intradermal MN) component /3, 5, 6, 9/. The evolution of MN is associated with the phases of melanocyte involution: melanocyte - nevus cell - fibrous tissue /10/.

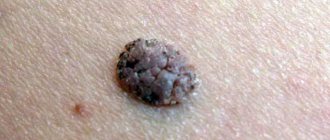

Clinically, borderline MN is manifested by a uniformly pigmented (from light brown to dark brown) spot with a diameter of 1-5 mm, round or oval in shape with a smooth surface and clear boundaries, located on any part of the skin and existing until approximately 35 years of age. Mixed MN is a pigmented papule, sometimes with papillomatosis, rarely reaching 1 cm in diameter. Intradermal MN is characterized by a dome-shaped or papillomatous papule, which in shape can resemble a blackberry (Fig. 1.), have a stalk or the shape of a mollusc-shaped element on a broad base (Fig. 2); its surface is covered with hair, its diameter rarely exceeds 1 cm, and its color varies from light brown to black. Rarely, depigmented MN with a whitish or pink-red color is found.

Rice. 1. Intradermal melanocytic nevus in the form of a blackberry.

Rice. 2. Intradermal melanocytic nevus mollusciform.

The dependence of the clinical picture of ordinary MNs on the localization and location of nevus cells in them was noted. Thus, on the palms and soles, the complex and intradermal MN (due to the large thickness of the stratum corneum) do not rise above the skin level; MNs raised above the skin level have a pronounced intradermal nevus component, and flat ones have a borderline component; The more the MN is raised above the skin level, the less pigmented it is.

Conventional MNs grow in proportion to the growth of the human body; after birth, their number increases, reaching a maximum during puberty, and after 50 years it gradually decreases, and by 7-9 decades of life they usually disappear. The regression of conventional MN is due to the degeneration of the cells that form it with their gradual replacement by fibrous and adipose tissue /10,24/. Sudden regression of such MNs occurs very rarely /29/.

The idea that melanoma-dangerous MN should include borderline and mixed forms (as those that retain a borderline component in their structure, including those localized in the area of the palms and soles, external genitalia, and nail bed) has now been revised. Thus, MN of the palms and soles, accounting for 4-9% of all MN, is currently not classified as melanoma-dangerous due to the fact that only dysplastic nevi of this localization transform into melanoma /17/. MN of the nail bed, the so-called longitudinal (linear) melanonychia in the form of pigmented lines running along the nail plate, can be not only borderline, mixed MN or acral-lentiginous melanoma, but also, often, the so-called “melanotic spot” (formed by increased melanin content in the cells of the basal layer of the epidermis without increasing the number of melanocytes) / 28 /. Although subungual melanoma occurs not only in adults but also in children, longitudinal melanonychia in children is almost always a benign process /21/.

Conventional MNs of the external genitalia are more often observed in young women in the area of the vulva and perineum, less often in the area of the male genital organs, but atypical histological signs are found in them extremely rarely (in 0.02% of cases) /27/. On the other hand, convincing evidence has been obtained that melanoma can develop both in the tissue of the intradermal MN and directly beneath it /30/.

Due to the possibility of developing melanoma against the background of intradermal MN, as well as due to the difficulty of clinically distinguishing borderline and mixed MN from dysplastic nevus, in order to avoid malignancy in ordinary MN, they should not be subjected to constant friction with clothing, contact with irritating substances, and mechanical hair removal from them is unacceptable. surface /25/.

Melanoma-dangerous MNs include congenital and dysplastic nevi. Congenital MN are benign pigmented tumors consisting of nevus melanoblast-derived cells. arising as a result of impaired differentiation of melanoblasts in the period between 10 weeks and 6 months of intrauterine life. They occur in 1% of Caucasian children, are detected at birth or during the first year of a child's life and come in different sizes: from tiny to gigantic. Any of them can develop melanoma. Clinically, they are light or dark brown in color, slightly raised above the skin level and sometimes covered with hair (hair growth does not begin immediately), and have a round or oval shape. Their boundaries are clear or blurred, the shape is regular or irregular, the surface has a preserved skin pattern or is bumpy, wrinkled, folded, lobulated, covered with papillae resembling cerebral convolutions (loss of skin pattern occurs when the reticular layer of the dermis is involved in the pathological process (blue congenital MN), color - light or dark brown. They are localized on any part of the skin and in 5% of cases they are multiple (in this case, one of them is large). Larger nevi have a soft consistency when palpated.

Congenital MNs can be small (up to 1.5 cm), large (up to 20 cm) and giant. Congenital MNs are practically indistinguishable from acquired conventional MNs, the only difference is a diameter of more than 1.5 cm (acquired MNs do not have such a diameter), therefore, it is currently proposed that MNs with a diameter of more than 1.5 cm be regarded as congenital MN or dysplastic nevus /2/. Large and giant congenital MNs, in contrast to small congenital MNs, which are solitary in 95% of cases, are usually represented by large or very large MNs, occupying part or all of the anatomical region (trunk, limb, head and neck), but in combination with many small ones MN (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3. Congenital melanocytic nevus.

In this case, nevus cells form ordered accumulations in the epidermis and dermis in the form of layers, nests or strands. The presence of nevus cells in the lower third of the reticular layer of the dermis or in the subcutaneous tissue indicates the congenital nature of MN /19/ Nevus cells are found, in contrast to acquired MN, also in the appendages of the skin, bundles of nerve fibers, muscles that raise the hair, in the walls of the blood and lymphatics vessels. In large and giant congenital MNs, nevus cells sometimes penetrate muscles, bones, and dura mater.

Unlike acquired MNs, congenital MNs do not disappear spontaneously. The risk of developing melanoma against the background of small congenital nevi is 1-5%, giant ones - 6.3% (and in 50% of cases, melanomas develop at the age of 3-5 years). The prognosis for melanoma growing from a large congenital MN is always unfavorable, since it is usually detected in the later stages of development.

Dysplastic nevus (DN) (syn.: Clark's nevus, atypical nevus) is an acquired pigmented neoplasm, characterized histologically by random proliferation of atypical melanocytes. It occurs in 5% of the population /8/ (including 30-50% of patients with sporadic and all patients with familial melanoma) and occurs on clinically unaffected skin or against the background of complex or (rarely) borderline MN. DNs appear later than acquired MNs—shortly before the onset of puberty or throughout life until old age. Their development is promoted by insolation. They are not characterized by spontaneous involution. DN can be sporadic (30-50% of cases) or hereditary, transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner (DN syndrome or familial atypical MN syndrome). DN syndrome and familial melanoma are caused by mutations of various genes, most often localized in chromosome segments 1p36 and 9p21 /19/. Clones of mutant melanocytes can be activated under the influence of photons from sunlight.

DN occupies an intermediate position between acquired MN and superficially spreading melanoma /2/ and is clinically manifested as: a spot with individual areas raised above the skin level (papule against the background of the spot), large (more than 15 mm in diameter) in size, uneven (motley, reminiscent of scrambled eggs - fried egg or target) coloring, asymmetry, irregular borders (the edges are partly fuzzy, uneven) (Fig. 4).

Rice. 4. Dysplastic nevus

Located mainly on the torso and limbs. Transformation of DN into superficial spreading melanoma occurs in 18-35% of cases /2.9/. The risk of developing melanoma in DN in persons with immunosuppression (organ transplant recipients, etc.) increases significantly, and in DN syndrome transformation into melanoma occurs in 100% of cases. It is estimated that in the presence of one DN, the likelihood of developing melanoma increases by 2 times, compared with cases where it is absent, and in the presence of 10 or more - by 12 times /2/. The risk of malignant transformation is especially high if a relative has more than 100 elements of DN or melanoma.

Histologically, DN is characterized by: hyperplasia and proliferation of melanocytes, which in the form of spindle-shaped cells are located in a single row along the basal layer of the epidermis (lentiginous melanocytic dysplasia) or in the form of epithelioid cells form scattered nests of irregular shape (epithelioid cell melanocytic dysplasia); atypical melanocytes (large cell size, polymorphism of cells and their nuclei, nuclear hyperchromasia); Nests of melanocytes are also characteristic: scattered, irregular in shape, forming “bridges” between the interpapillary processes of the epidermis; spindle-shaped melanocytes are oriented parallel to the skin surface; there is a proliferation of collagen fibers in the dermal papillae and fibrosis (a variable sign) / 19 /.

In connection with the problem of melanoma formation in melanoma-dangerous MN, it is important to take into account that its cytological diagnosis is not sufficiently reliable, therefore, for the purpose of diagnosis and differential diagnosis, a diagnostic biopsy of the neoplasm is performed.

Excisional biopsy for the purpose of histological examination, a reliable method for detecting melanoma, is safe and recommended for MNs less than 1.5 cm in diameter and carried out 2 mm from its edge /4.12/.

An incisional (partial) biopsy is performed by an oncologist for very large (congenital) MNs /4/. In particular, with the sudden appearance of longitudinal melanonychia, to exclude acral-lentiginous melanoma or Bowen's disease of the nail matrix (also causing longitudinal melanonychia), a biopsy is performed with a 3-4 mm punch (through the nail plate and matrix to the phalangeal bone) /26/.

Superficial biopsy (“cutting”, curettage, etc.) is unacceptable, because does not make it possible to determine the depth of tumor invasion /19/.

Differential diagnosis of MN with various dermatoses and skin neoplasms is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

To the differential diagnosis of melanocytic nevus

| Form MN | Dermatosis/skin tumor |

| Border | Freckles, lentigo simplex, lentigo solar (senile), café au lait spots, congenital MN, macular nevus, xeroderma pigmentosum, dysplastic nevus, Dubreuil's melanosis. |

| Mixed | Seborrheic keratosis, Kaposi's sarcoma |

| Intradermal | Dermatofibroma, wart vulgaris, trichoepithelioma, juvenile xanthoma, syringoma, molluscum contagiosum, accessory nipple, pyogenic granuloma, neurofibroma, acrochordon, cystic basal cell carcinoma |

| Congenital | Dysplastic nevus, blue nevus, Becker's nevus, verrucous epidermal nevus, café au lait spots |

| Dysplastic nevus | Congenital MN, Dubreuil's melanosis, Spitz nevus, pigmented basal cell carcinoma |

The differential diagnosis of MN with Dubreuil's precancerous limited melanosis and some forms of melanoma should be discussed in more detail.

Precancerous melanosis limited by Dubreuil (syn.: Hutchinson's melanotic freckle), in contrast to intradermal MN, has a larger (over 20 mm) diameter, irregular outline, uneven pigmentation; it occurs on exposed areas of the skin (usually on the cheeks in older people) and is characterized by slow progression to melanoma; Histological examination reveals the structure of melanoma in situ.

Acral-lentiginous melanoma, in contrast to intradermal MN, is characterized by a brown or black plaque with unclear contours and uneven coloring /2/.

Desmoplastic (amelanotic) melanoma, in contrast to intradermal MN, looks like a non-pigmented spot or papule, reminiscent of a scar or scar, and in the “vertical growth” phase it is characterized by a dense node, most often developing in the head and neck area in people of the 6th-7th decade life, may occur in association with acral-lentiginous melanoma or de novo /14/; microscopically consists of spindle-shaped cells located between thin layers of collagen, which are often formed into bundles.

Differential diagnosis of intradermal MN with superficial spreading and nodular forms of melanoma is carried out according to the “FIGARO” rule:

F - shape. Melanoma is characterized by a convex shape (which is best seen in side lighting). Melanoma in situ and acral lentiginous melanoma are flat.

And - change in size. Accelerated growth is one of the most important signs of melanoma.

G - the boundaries are incorrect. The tumor has “ragged” edges.

A- asymmetry - one half of the tumor is not similar to the other.

P - large sizes (usually more than 6 cm)

O- the color is uneven - randomly scattered brown, black, gray, pink and white areas /9/.

Dark brown and black MNs in people with fair skin color should be considered the most suspicious for melanoma. You should also be suspicious of MN with bluish, reddish and white areas on the surface. However, changes in the color of MN may be due to factors not related to its malignant transformation: pregnancy, puberty, taking glucocorticoid hormones, exposure to external factors, including solar radiation. In such cases, all MNs or MNs of the same localization that were affected by external factors change simultaneously. Only changes in a single MN require oncological alertness.

When collecting anamnesis, the dermatologist must exclude other causes of sudden changes in MN that are not related to its transformation into melanoma. Thus, a sudden change in color, surface or size in the presence of pain, itching, ulceration and bleeding can be caused by the formation of a cystic enlargement of the hair follicle, an epidermal cyst in the MN, the development of folliculitis in it, as well as trauma, hemorrhage, compression or thrombosis of skin vessels. With such changes, dynamic observation is required with serial photography of the elements until the effects of injury or inflammation pass (usually 7-10 days), and in some cases a histological examination is required.

Among the instrumental methods for excluding melanoma, epiluminescence microscopy is currently used - a non-invasive method for studying skin formations in a special immersion environment using a dermatoscope, as well as a computer diagnostic method in which images recorded using a digital video camera are stored in computer memory and compared with the existing one based on certain characteristics. database /1/.

The accuracy of histological diagnosis of melanogenic skin tumors increases when using the “diagnostic ploidometry” method /10/.

Treatment tactics

Although in the vast majority of cases acquired MN do not require treatment, it is still undertaken in some conditions.

Indications for excision of conventional MNs may include:

- the patient’s desire to remove it for cosmetic reasons, however, it should be taken into account that histological preparations of “disfiguring MN” often reveal atypical cells /25/;

- location in places difficult for self-control (scalp, perineum, etc.), this primarily applies to hyperpigmented MN and if there is a personal or family history of DN;

— presence of signs of atypia in the MN: uneven distribution of pigment, jagged and unclear boundaries, relatively large size (more than 5 mm);

- atypical evolution of MN, including a sudden change in size and shape /13/;

— MN with a high risk of malignancy (lentigo maligna, giant congenital MN); DN, including as part of spotted MN; prophylactic removal prevents the possibility of melanoma even with a significant number of MNs /25/;

- although the features of the anatomical location are not considered as an indication for removal of MNs, nevertheless, intensely pigmented MNs of acral localization in the extremities, as well as on the mucous membrane, should be removed, as well as MNs of the subungual region and conjunctiva, since the possibility of DN of such localization should cause caution regarding its transformation into melanoma /22/.

If the element is frequently repeatedly irritated, it is better to remove it than to miss melanoma or other malignant tumor /11/; at the same time, MNs located under a belt, bra, or collar do not have to be removed if they look benign /25/;

Based on this, the MN can be surgically removed in case of: rapid change in the element, atypical clinical picture, suspicious for melanoma, for cosmetic reasons, repeated injury to the element /13/.

The indication for immediate excision of the MN is the presence of at least one of 7 signs of its sudden (within one or several months) change:

- increasing the area and height of the element;

- increasing the intensity of pigmentation, especially if it is uneven;

- signs of local regression;

- the appearance of a pigment corolla around the MN, the appearance of satellite elements;

- inflammatory reaction in the MN;

- itching;

- erosion and bleeding.

Removal of MN must be complete and performed surgically with mandatory histological examination. After partial removal, the MN repigments and recurs, forming pseudomelanoma /23/. Other removal methods (electrocoagulation, cryodestruction, dermabrasion, laser) for pigmented formations of the skin and mucous membranes should not be performed, because do not provide documentary verification of the diagnosis /12/.

When starting treatment for MN, it should be taken into account that with its non-radical removal, the cosmetic outcome is often unpredictable, because treatment may lead to relapse with less favorable consequences than before treatment /25/.

All small congenital MNs that look unusual (uneven coloring, irregular outline, etc.) are subject to surgical removal before the patient reaches the age of 12 years. Giant congenital MN is removed as early as possible. Full-thickness skin flaps are used to close the defect. For large sizes, they resort to expander plastic or plastic with local tissues.

Treatment of DN should be carried out by an oncologist.

Prevention of melanoma consists of early and active detection of pre-melanoma lesions (primarily DN and lentigo maligna), the need to allocate patients with their presence to a “risk group” with constant dynamic monitoring of macroscopic changes in these spots.

Patients with DN should be informed about the signs of transformation of these MNs into melanoma and independently regularly monitor the nature of individual elements. They are advised to avoid exposure to the sun and use sunscreen (Anthelios XL60+) when going outside.

V.A. Molochkov

Moscow Regional Research Clinical Institute named after M.F. Vladimirsky)

Molochkov Vladimir Alekseevich - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Clinic of Dermatovenereology and Dermato-Oncology

Literature:

1. Demidov L.V., Kharkevich G.Yu. Markina I.T. and others. Melanoma and other malignant neoplasms of the skin/Encyclopedia of Clinical Oncology. Guide for practitioners / M.I. Davydov et al. - M.: RLS-2005.-P.341-364;

2. Borisova G.N., Kudryavtseva G.T. //Vestn. dermatol.-2006.-No.3.-P.43-45;

3. Dermato-oncology /Ed. G.A. Galil-ogly and others - Medicine for all - 2005;

4. Makin I.L.. Pshenistov K.P. Selected issues of plastic surgery-1999.-No. 1-Yaroslavl-DIA-press;

5. Molochkov V.A. //Aesthetic Medicine-2005.-No. 3-P.266-270;

6. Molochkov V.A. //Russian Journal of Skin and Venereal Diseases-1998.-No.2.-P.68-76;

7. Organizational technology of interaction between dermatovenerological and oncological services to provide specialized care to patients with pre-tumor and malignant skin pathologies - Guidelines No. 2003/60-M, 2003;

8. Paltsev M.A., Potekaev N.N., Kazantseva I.A. and others. Clinical and morphological diagnosis of skin diseases (atlas) - M.: Medicine-2004;

9. Fitzpatrick T., Elling D.L. Secrets of dermatology /Trans. from English - M.S.Pb - BINOM - Nevsky dialect - 1999;

10. Chervonnaya L.V. Diagnosis of skin tumors of melanocytic origin // Abstract. dis. .. doc. medical sciences-2003;.

11. Chissov V.I., Romanova O.A., Moiseev G.F. Early diagnosis of melanoma. - M.: Yulana Trade, 1998;

12. Anderson RG //Select. Read. Plast. Surg.-1992.-Vol.7.-P.1-35;

13. Barnhill RL, Lewellin K. Benigh Melanocytic Neoplasm /In: Dermatology /Ed. J.Bolognia et al.-Mosby-Edinburg-2003.-P.1757-1787;

14. Barnbill RL, Mihm MC Histopathology and precursor lesions /In: Cutaneous melanoma, 3ed/Ed. CM Balch et al.-St.Louise, Quality Medical.-1998.-P.103-133;

15. Bhawan J.//Cutan Pathol.-1979.-Vol.6.-P.153;

16. Bogdan I., Smolle J., Kerl H. et al.//Melanoma Res.-2003.-Vol.13.-P.213-217:

17. Clemente C., Zurrida S., Bartoli D. et al. //Hitopathology-1998.-Vol.27.-P.549-555;

18. Crulich AE et al.//Int.J.Cancer-1996.-Vol.67.-P.485;

19. Elder DE, Elenitsas R., Murphy GF, Xu X. Benign pigmented lesions and malignant melanoma / Lever's Histopathology of the Skin .Ed.: DEElder-9th ed- Lippincott Williams & Wilkins-Philadelphia-2005.-P.715-803 ;

20. Eskandrapour M., Hashemi J., Kanter L. et al. Frequency of UV-inducible NRAS mutations in melanomas of patients with germline CDKN2A mutations //J.Natl.Cancer Inst.-2003.-Vol.95.-P.790-798;

21. Goettman-Bonvallot S., Andre J., Belaich S. // J.Am.Acad. Dermatol.-1999.-Vol.41.-P.17-22;

22. Kopf AW, Waldo E.//Aust.J.Dermaatol.-1980.-Vol.21.-P.59;

23. Kornberg R., Ackerman AB//Arch.Dernatol.-1975.-Vol.111.-P.1588;

24. Maize JC, Foster G. //Clin. Exp. Dermatol. - 1979. - Vol.4. - P.49;

25. Rhodes AR Benign neoplasias and hyperplasias of melanocytes //Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine - 5th ed.//Ed. IMFreedberg et al. —Mc Graw-Hill-New York. - 1999. - P.1018-1059;

26. Rich P. //J.Dermatol.Surg.Oncol.-1992.-Vol.18.-P.673-682;

27. Rock B., Hood AF, Rock JA // J.Am.Acad. Dermatol.-1990.-Vol.22.-P.104-106;

28. Scher RK, Silvers DN // J.Am.Acad. Dermatol.-1991.-Vol.24. -P.1035-1036;

29. Shelly WB //Arch. Dermatol.-1960.-Vol.81.-P.208;

30. Tajima Y., Nakaijama T., Sagano I. et al //Am.J.Dermatopathol-1994.-Vol.16.-P.301-306.

What to do? Should I delete or not?

Fortunately, I was not able to find practical recommendations in which the mere presence of an atypical nevus on a person’s skin would be considered a direct indication for its removal.

On the other hand, the presence of single or multiple, atypical [7] and dysplastic [3] nevi on a person’s skin equally increases the risk of developing melanoma on the skin as a whole.

Thus, in my opinion, the most logical tactic seems to be not prophylactic removal of atypical nevi, but increasing the frequency of preventive self-examinations and examinations by an oncologist.