Why does mastocytosis occur?

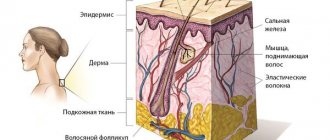

To begin with, mastocytosis is caused by an excessive accumulation of mast cells. What are mast cells? Mast cells are a type of white blood cell that play a critical role in the development of inflammation and allergic reactions. When there is some kind of threat to the body, for example, an infection, an allergen or a toxin, etc., mast cells release special mediators - biologically active substances that trigger a protective reaction in the body. For example, one of these “defenders” is histamine, which triggers an immediate allergic reaction: itching, swelling and redness.

Mastocytosis causes an excess of mast cells, which abnormally multiply and accumulate in tissues and organs. Why this happens is still completely unknown.

Trigger factors for the development of mastocytosis can be any reason that can cause an allergic reaction, including stress, cold, heat, and excess ultraviolet radiation. An excessive number of mast cells leads to the release of a large number of mediators, including histamine.

Symptoms of mastocytosis

Half of patients diagnosed with mastocytosis complain only of skin lesions. When internal organs are affected, symptoms include a periodic drop in blood pressure, paroxysmal redness of the skin, causing an itching sensation. Paroxysmal tachycardia is also a manifestation of the disease.

Infiltrates from mast cells, characteristic of mastocytosis, can be grouped in a variety of layers of the skin. Accordingly, there are several clinical variants of the symptoms of skin lesions with mastocytosis:

- Maculopapular type of mastocytosis. It is characterized by multiple hyperpigmented areas appearing on the skin. In addition, there are lesions with a very clear contour. The Daria-Unna phenomenon is clearly manifested: friction of even a healthy area of skin leads to the formation of blisters and other changes similar to the manifestation of urticaria. Therefore, the maculopapular type of mastocytosis is also called urticaria pigmentosa.

- Nodular type of mastocytosis. The symptoms of this type of disease manifest themselves in a variety of dense neoplasms, nodules, and balls. The diameter of such a rash reaches one centimeter. The color of the nodules is yellow, red, crimson, pink. These neoplasms tend to merge, forming plaques with a smooth surface or a coating resembling an orange peel. Large plaques have a bumpy surface. In this type of disease, the Daria-Unna phenomenon is present, but weakly manifested.

- Solitary type of mastocytosis. Symptoms include the formation of a single node with a diameter of up to five centimeters, which feels like rubber to the touch. The surface of such a node can be smooth or wrinkled. The solitary form of mastocytosis involves the formation of a single node, however, some clinical forms can be detected in three or four such neoplasms. Single nodes can be combined with a maculopapular rash, and they develop only in the case of cutaneous mastocytosis. The nodes are localized on the torso, neck, and forearms. If such a neoplasm is injured, then bubbles form on its surface, this is how the Daria-Unna phenomenon manifests itself. Nodes can disappear on their own, leaving no trace.

- Erythrodermic type of mastocytosis. It is characterized by yellow-brown skin lesions with uneven outlines and a dense consistency, accompanied by severe itching. Over time, scratches, cracks, wounds, ulcers, and scratches appear on the surface of the affected areas of the skin. Most often, these rashes are concentrated in the fold between the buttocks and armpits. The Daria-Unna phenomenon manifests itself actively in the erythrodermic type of mastocytosis. Trauma to the affected area of the skin leads to active formation of blisters and even more severe itching. If a lot of blisters appear, then the presence of a bullous form of the disease is stated. Erythrodermic mastocytosis can develop into erythroderma.

- Telangiectatic type of mastocytosis. Symptoms of this form of the disease include brown and red skin lesions. Usually localized on the limbs and chest. This form of mastocytosis is most common in women.

Forms and symptoms of the disease

The disease most often appears before the age of 3 years.

Mastocytosis appears differently depending on the form of the disease.

The most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis in children and adults is urticaria pigmentosa , also known as maculopapular mastocytosis.

Maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis accounts for 70-90% of all cases of cutaneous mastocytosis in children. At the same time, 80% of children with urticaria pigmentosa develop initial skin lesions in the first year of life, the disease is diagnosed by 2 years.

The following symptoms are typical for urticaria pigmentosa:

- the presence of yellow-brown or reddish-brown spots, or slightly raised papules, which may at first be mistaken for freckles;

- as a rule, the upper and lower extremities, chest and abdomen are affected;

- childhood mastocytosis is characterized by damage to the face and scalp;

- in adults, areas of the skin such as palms, soles, scalp and others exposed to the sun do not develop rashes;

- itching

The following factors can aggravate the course of urticaria pigmentosa:

- temperature changes can provoke and aggravate skin itching,

- physical exercise,

- hot shower,

- local friction,

- drinking hot drinks,

- spicy food,

- ethanol,

- emotional stress,

- some types of medicines.

Systemic mastocytosis , another form of mastocytosis that affects other organs, is relatively less common: approximately 10% of all cases of mastocytosis in children.

Symptoms of systemic mastocytosis:

- skin rash,

- changes in clinical blood test,

- enlargement of the liver and spleen,

- enlarged lymph nodes,

- A blood test will show elevated serum total tryptase, which is a major marker of mast cell activation.

If the diagnosis does not show an enlargement of the liver and spleen, as well as lymph nodes, laboratory tests are normal, then observation of this condition is required.

In some cases, in young children, enlarged lymph nodes may be the norm, just like thrombocytosis - these indicators can normalize over time.

Mast cell accumulation factors:

- Medicines: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; iodine-containing contrast agents; vancomycin and muscle relaxants, which are used in anesthesia; as well as opioids and narcotics.

- Physical: massage, friction; physical exercise; sudden changes in temperature, including the application of extreme temperatures to the skin; spicy food.

- Surgical interventions, including biopsy and endoscopy.

- Infections: viral, bacterial, parasitic.

- Emotional stress.

- Hymenoptera bites.

- Toxic effects: jellyfish, snake stings.

Also, patients with mastocytosis may experience concomitant allergic diseases:

- allergic rhinitis,

- bronchial asthma,

- food or drug allergies,

- allergic reactions to Hymenoptera bites.

Mastocytosis is characterized by the presence of daily symptoms that significantly reduce the child’s quality of life.

These symptoms are:

- itching, turning into hyperemia, erythema, swelling and dermatographism;

- with diffuse skin lesions and mastocytoma in children, blisters and blisters may occur;

- With systemic mastocytosis, daily symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, and low blood pressure.

Important! A mastocytosis rash should not be rubbed or scratched, as this can cause even more mast cells to be released, leading to generalized redness and hives!

Mastocytosis: clinical manifestations, diagnostic methods and patient management tactics

Mastocytosis is a group of diseases caused by the accumulation and proliferation of mast cells in tissues [1]. It was first described by E. Nettleship and W. Tay in 1869 as a chronic urticaria that left brown spots. In 1878, A. Sangster proposed the term “urticaria pigmentosa” to refer to such rashes. The nature of these rashes was revealed in 1887 by the German dermatologist P. Unna as a result of histological studies. In 1953, R. Degos introduced the term “mastocytosis.”

Mastocytosis is a fairly rare disease. In the Russian Federation, there are 0.12–1 cases of mastocytosis per 1000 patients [2]. Pediatric dermatologists see these patients more often. Thus, in the international guide to dermatology “Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. Clinical Dermatology” indicate a ratio of 1 case per 500 pediatric patients [3]. Perhaps in the Russian Federation there is an underdiagnosis of mastocytosis. Both sexes are affected equally often. Mastocytosis in children accounts for a significant portion, and in children, mastocytosis is usually limited to skin lesions, while in adults, systemic mastocytosis (SM) more often develops. Knowledge of the manifestations of SM and the management tactics of such patients helps to prevent possible serious complications that can accompany not only aggressive SM, but also cutaneous, non-systemic mastocytosis, which occurs benignly. Such complications include anaphylaxis, urticaria and angioedema, gastrointestinal disorders, etc.

Biology of mast cells and etiopathogenesis of mastocytosis

The etiology of the disease is unknown. Mast cells were first described by P. Ehrlich in 1878 and named so because of the special coloring of large granules. The appearance of these granules led scientists to mistakenly believe that they existed to feed surrounding tissues (hence the cells' name "Mastzellen", from the German Mast, or "fattening" of animals). Currently, mast cells are considered to be very powerful cells of the immune system, involved in all inflammatory processes and especially IgE-mediated mechanisms.

Mast cells are widespread in almost all organs. They are located close to blood and lymphatic vessels, peripheral nerves and epithelial surfaces, which allows them to perform various regulatory, protective functions and participate in inflammatory reactions. Mast cells develop from pluripotent bone marrow progenitor cells that express the CD34 antigen on their surface. From here they disperse as precursors and undergo proliferation and maturation in specific tissues. Normal mast cell development requires interactions between mast cell growth factor, cytokines, and c-KIT receptors, which are expressed on mast cells at various stages of their development. Mast cell growth factor binds the protein product of the proto-oncogene c-KIT. In addition to stimulating mast cell proliferation, mast cell growth factor stimulates melanocyte proliferation and melanin synthesis. This is associated with hyperpigmentation of skin rashes with mastocytosis. Mast cells can be activated by IgE-mediated and non-IgE-dependent mechanisms, resulting in the release of various chemical mediators that accumulate in secretory granules; at the same time, the synthesis of membrane lipid metabolites and inflammatory cytokines occurs (tryptase, histamine, serotonin; heparin; thromboxane, prostaglandin D2, leukotriene C4; platelet activating factor, eosinophil chemotaxis factor; interleukins-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6; and etc.) [4]. The episodic release of mediators from mast cells that have undergone excessive proliferation leads to a wide range of symptoms. Such hyperproliferation may represent reactive hyperplasia or a neoplastic process. Disturbances of c-KIT receptors or overproduction of their ligands possibly lead to disordered cell proliferation. A mutation in the c-KIT gene locus causes constitutional activation and increased expression on mast cells. It is this clonal proliferation that is believed to play a major role in the pathogenesis of mastocytosis [5].

Two types of mutations are known that lead to the development of mastocytosis in adults: mutation of the c-KIT proto-oncogene (most often) and other mutations (Table 1). The protein of this gene is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (CD117), the ligand of which is a stem cell factor (mast cell growth factor). A mutation in codon 816 of the named proto-oncogene leads to tumor transformation of mast cells. Rarely, other c-KIT mutations can be found [1] (Table 1).

Another mutation may occur on chromosome 4q12 in the form of a deletion of this region of the chromosome. This leads to pathological juxtaposition of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha gene and the FIP1L1 gene. As a result of the fusion of these genes, activation of hematopoietic cells and hyperproliferation of mast cells and eosinophils occurs. The same mutation causes the development of hypereosinophilic syndrome.

The above gene mutations are rarely observed in children. The disease, as a rule, is not familial, with the exception of rare cases of autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced expressivity (Table 1). Mastocytosis in children is associated with spontaneous cases of cytokine-mediated mast cell hyperplasia, c-KIT gene mutations other than codon 816, or other as yet unknown mutations.

According to the 2005 Consensus on Mastocytosis Standards and Standardization [1], the following markers should be determined in the biopsy specimen:

1) CD2 - T-cell surface antigen (normally found on T-lymphocytes, natural killer cells, mast cells). The absence of this antigen on mast cells suggests that mast cell infiltration is not associated with mastocytosis;

2) CD34 is an adhesion molecule marker expressed on mast cells, eosinophils, and stem cells;

3) CD25 is the alpha chain of interleukin-2, expressed on activated B and T lymphocytes, on some tumor cells, including mast cells. CD25 is a marker of SM;

4) CD45 is a common leukocyte antigen present on the surface of all representatives of the hematopoietic series, except for mature erythrocytes. Normally located on the surface of mast cells;

5) CD117 - transmembrane receptor c-KIT, located on the surface of all mast cells;

6) antibodies to tryptase.

Classification of mastocytosis

The modern classification of mastocytosis was proposed by C. Akin and D. Metcalfe, which is considered the WHO classification (2001) (Table 2) [3].

Clinic and diagnosis of mastocytosis

There are cutaneous and systemic mastocytosis. The cutaneous form affects mainly children and rarely adults. Infantile mastocytosis is divided according to its prevalence into the following three categories: the most common form (60–80% of cases) is urticaria pigmentosa; cases of solitary mastocytoma are observed less frequently (10–35%); even rarer forms are diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis or telangiectatic type. The disease usually occurs during the first two years of a child's life (75% of cases). Fortunately, cutaneous mastocytosis in children is prone to spontaneous regression [2]. A significant proportion of adult patients have SM, as they typically have clonal proliferation of mast cells from the bone marrow. Among adults with SM not associated with hematologic disease, 60% have indolent disease and 40% have aggressive mastocytosis (such patients usually do not have cutaneous manifestations). Symptoms of SM are determined depending on the location of infiltrates and mediators released by mast cells, and include: itching, flushing (sudden redness of the skin, especially the face and upper body), urticaria and angioedema, headaches, nausea and vomiting, paroxysmal abdominal pain , diarrhea, duodenal and/or gastric ulcers, malabsorption, asthma-like symptoms, presyncope and fainting conditions, anaphylaxis. These symptoms may occur spontaneously or be the result of factors that promote mast cell degranulation (eg, drinking alcohol, morphine, codeine, or rubbing large areas of skin). Insect bites can often cause anaphylaxis in such patients. Hyperreactivity to some nonspecific factors (for example, taking Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cold, contact with water), causing pronounced manifestations of acute recurrent or chronic urticaria, may also be a manifestation of SM. In the blood of such patients there is no increase in the level of total IgE and specific IgE antibodies are rarely detected, since such patients may not have allergies more often than the general population. At the same time, a consistently elevated level of tryptase in the blood is a sign of SM. Since mast cells produce heparin, this can lead to nosebleeds, hematemesis, melena, and ecchymosis. Spontaneous fractures due to osteoporosis are more common in patients with SM. Osteoporosis is probably caused by an imbalance between osteoblasts and osteoclasts towards activation of the latter under the influence of heparin [6].

Some authors propose to include another disease in the classification of mastocytosis - “bone marrow mastocytosis”. With this isolated variant of mastocytosis, there is a low content of mast cells in other tissues, a low level of tryptase in the blood and a good prognosis. This disease can be suspected in cases of unexplained signs of anaphylaxis, osteoporosis of unknown etiology, unexplained neurological and constitutional symptoms, unexplained intestinal ulcers or chronic diarrhea [1].

The differential diagnosis of mastocytosis is very wide and depends on the manifestations of the disease (Table 3) [7].

Let us dwell in more detail on the cutaneous form of mastocytosis.

Cutaneous mastocytosis

Typically, the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis is not difficult for an experienced dermatologist. However, the author of the article has repeatedly encountered misdiagnosis of this disease in both children and adults. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children manifests itself in three forms: solitary mastocytoma; urticaria pigmentosa and diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (the latter is extremely rare). A combination of these forms in the same child is possible. In children, as a rule, the diagnosis is made on the basis of the clinical picture, without histological examination. This is justified by the fact that in children, cutaneous mastocytosis usually resolves spontaneously within several years. However, since we are talking about a proliferative disease of a hematological nature, it is always better to conduct a histological and immunohistochemical examination of the biopsy specimen. It is especially important to carry out such an analysis in cases where the rash appeared after the age of 15 years (manifestation of SM). P. Valent et al. [1] indicate the following criteria for the diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis: typical clinical manifestations (major criterion) and one or two of the following minor criteria: 1) monomorphic mast cell infiltrate, which consists of either aggregates of tryptase-positive mast cells (more than 15 cells per cluster), or - scattered mast cells (more than 20 in the field of view at high (×40) magnification); 2) detection of c-KIT mutation at codon 816 in biopsy tissue from the lesion.

P. Vaent et al. [1] proposed to determine the severity of cutaneous manifestations of mastocytosis. In addition to assessing the area of skin lesions, the authors propose to distribute the severity of rashes into five degrees, depending on the presence of concomitant symptoms that may accompany skin manifestations - itching, flushing and blistering (Table 4).

| Rice. 1. Urticaria pigmentosa in a child (a surface resembling an orange peel is noticeable) |

| Rice. 2. Urticaria pigmentosa in the same child (in the area of the right shoulder blade - erosion after a burst bladder) |

Children's type of generalized rash (urticaria pigmentosa)

This form of cutaneous mastocytosis occurs in 60–90% of cases of mastocytosis in children. In this case, the rash appears during the first weeks of the child's life and appears as pink, itchy, urticarial, slightly pigmented spots, papules or nodules. The rashes are oval or round in shape, ranging in size from 5 to 15 mm, and sometimes merge with each other. The color varies from yellow-brown to yellow-red (Fig. 1, 2). Occasionally, the rashes may be pale yellow in color (they are also called “xanthelasma-like”). The formation of vesicles and blisters is an early and fairly common manifestation of the disease. They may be the first manifestation of urticaria pigmentosa, but never last more than three years. At older ages, vesiculation is very rare.

Usually, at the beginning of the disease, the rash looks like urticaria, with the difference that urticaria are more persistent. Over time, the rash gradually turns brown. When the skin is irritated in the area of the rash, urticaria appear on an erythematous background or blisters (positive Darier's sign); A third of patients have urticarial dermographism. Hyperpigmentation remains for several years until it begins to fade. All manifestations of the disease usually disappear by puberty. Rarely do rashes persist into adulthood. Although systemic involvement is possible, malignant systemic disease is extremely rare in this form of mastocytosis [3].

Solitary mastocytoma

Between 10% and 40% of children with mastocytosis have this form of the disease. Solitary (single) rashes may be present at birth or develop during the first weeks of a child's life. As a rule, these are brownish or pink-red edematous papules that form a blister when the skin is irritated (positive Darier's sign). It is not uncommon to see several mastocytes on a child’s skin (Fig. 3). Mastocytomas may also appear as papules, raised round or oval plaques, or as a tumor. The sizes are usually less than 1 cm, but can sometimes reach 2–3 cm in diameter. The surface is usually smooth, but may have an orange peel appearance. Mastocytoma can be located in any location, but the dorsal surface of the forearm, near the wrist joint, is more common. Edema, urticaria, vesiculations, and even blisters may be found along with mastocytoma. A single mastocytoma may produce systemic symptoms. Within three months from the date of the first mastocytoma, such rashes may spread. Mastocytomas can be combined with urticaria pigmentosa in the same child (Fig. 4). Most mast cellomas regress spontaneously within ten years. Individual formations can be excised. It is also recommended to protect rashes from mechanical stress using hydrocolloid dressings. Progression to malignancy does not occur.

| Rice. 3. Multiple mastocytomas | Rice. 4. Urticaria pigmentosa in the same child (with mastocytomas) |

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis

The disease is rare, manifests itself in the form of a continuous infiltrated surface of the skin of a special orange color, called “home orange” (French “orange man”). Upon palpation, a doughy consistency is determined, sometimes lichenification. This is due to diffuse infiltration of the dermis by mast cells. In infancy, widespread blistering rashes are possible, which are mistakenly diagnosed as congenital epidermolysis bullosa or other primary blistering dermatoses. This phenomenon is called “bullous mastocytosis”.

Clinical forms of cutaneous mastocytosis in adults

Typically, cutaneous manifestations of mastocytosis in adults are part of a sluggish (indolent) SM [1]. The exception, perhaps, is macular eruptive persistent telangiectasia, especially if it appeared in childhood, which most often is a dermatosis without systemic manifestations. However, even in this case, the patient should be examined for SM. In addition to routine examination, histological and immunohistochemical examination of the skin from the lesion, bone marrow examination, determination of serum tryptase levels, abdominal ultrasound and chest x-ray should be performed. If lymph node involvement is suspected, it is advisable to use positron emission computed tomography.

Generalized cutaneous mastocytosis, adult type

The most common cutaneous form of mastocytosis in adults. The rashes are generalized, symmetrical, monomorphic, represented by spots, papules or nodules of dark red, purple or brown color (Fig. 5, 6). Rarely, they may resemble common acquired melanocytic nevi. There are no subjective symptoms. A positive Daria sign is possible.

| Rice. 5. Generalized cutaneous macular mastocytosis of adults | Rice. 6. Generalized cutaneous macular mastocytosis of adults |

Erythrodermic form of mastocytosis

Erythroderma, which has the appearance of “goose bumps”. Unlike diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis in children, the skin color does not have the characteristic orange color and infiltration is less pronounced. Blisters occur in various parts of the body.

| Rice. 7. Macular eruptive persistent telangiectasia. Multiple small hyperpigmented spots against a background of erythema without subjective sensations |

Telangiectasia macular eruptive persistent

Rash in the form of generalized or widespread erythematous spots that are less than 0.5 cm in diameter, with a slight red-brown tint. Despite the name, there is little or no telangiectasia in this form of mastocytosis (Fig. 7). The rash is not accompanied by subjective sensations; Daria's sign is negative. Unlike other cutaneous manifestations of mastocytosis in adults, this disease is rarely associated with SM. However, as with other forms of cutaneous mastocytosis in adults, screening to rule out systemic involvement, including a bone marrow biopsy, is necessary.

Systemic mastocytosis

For laboratory diagnosis of SM, it is necessary to have at least one major and one minor criterion or 3 minor criteria from the following.

The main criterion is a dense infiltration of mast cells (15 or more cells) in the bone marrow or tissue other than the skin.

Minor criteria:

1) atypical mast cells;

2) atypical mast cell phenotype (CD25+ or CD2+);

3) tryptase level in the blood is higher than 20 ng/ml;

4) the presence of a mutation in codon 816 of c-KIT in peripheral blood cells, bone marrow or affected tissues [1].

Despite the fact that mastocytosis is usually limited to skin lesions in children, the level of tryptase in the blood should be examined at least once in each child in connection with the possibility of developing SM. In this case, you should make sure that the child has not had an immediate allergic reaction within 4-6 weeks. If the serum tryptase level is from 20 to 100 ng/ml, without other signs of SM, indolent SM should be assumed and the child should be followed until puberty for this diagnosis. In this case, the child does not need a bone marrow biopsy. If the tryptase level is above 100 ng/ml, it is necessary to conduct a bone marrow test. In cases where it is not possible to examine the level of tryptase in the blood, the decisive criterion may be ultrasound data of the liver and spleen: the presence of enlargement of the liver and/or spleen should serve as a basis for a bone marrow examination. Of course, testing the level of tryptase is a more objective indicator that should be preferred for diagnosis.

Sluggish (indolent) systemic mastocytosis

The most typical form of SM in adults is indolent systemic mastocytosis. These patients do not have manifestations of hematological diseases associated with SM, as well as organ dysfunction (ascites, malabsorption, cytopenia, pathological fractures) or mast cell leukemia. The skin rashes described above are common, and systemic symptoms may sometimes occur, especially when exposed to mast cell triggers. This disease is diagnosed based on clinical, histological and immunohistochemical findings of the affected skin, as well as monitoring of serum tryptase levels. Organ damage is indicated by bone marrow infiltration, where at least 30% are mast cells, blood tryptase levels greater than 200 ng/ml, and hepatosplenomegaly [3].

Systemic mastocytosis associated with hematologic disease (non-mast cell)

As a rule, patients with SM associated with hematological pathology are elderly people with various systemic symptoms (~30% of cases of SM diseases). Hematological pathology may include: polycythemia vera, hypereosinophilic syndrome, chronic myelo- or monocytic leukemia, lymphocytic leukemia, primary myelofibrosis, lymphogranulomatosis.

The most common concomitant pathology is chronic monomyeloid leukemia. Less commonly, lymphoid neoplasia (usually B-cell, for example, plasma cell myeloma). Typically, such patients do not have skin rashes. The prognosis depends on the concomitant disease, but the presence of SM worsens the prognosis.

In the case of SM with eosinophilia, in which a constant increase in the number of eosinophils in the peripheral blood is determined (more than 1500 in one μl of blood), the final diagnosis can only be made on the basis of DNA analysis. Other signs are of auxiliary importance. For example, the presence of the FIP1L1/PDGFRA gene (two genes that have undergone fusion with each other) and/or deletion of the CHIC2 gene makes it possible to diagnose “SM with chronic eosinophilic leukemia.” In patients with clinical signs of chronic eosinophilic leukemia, in whom the above clonal disorders have not been confirmed, the diagnosis is changed to “SM with hypereosinophilic syndrome.” When assessing the clinical picture of the disease, it should be borne in mind that SM with eosinophilia can lead to fibrosis of the lungs and myocardium only at a very late stage, in contrast to hypereosinophilic syndrome [1]. This confirms how difficult the diagnosis of SM is, especially in the context of limited laboratory diagnostic capabilities in the periphery.

Aggressive systemic mastocytosis

Aggressive adult SM has a more fulminant course, with target organ dysfunction due to mast cell infiltration (bone marrow failure, liver dysfunction, hypersplenism, pathological fractures, gastrointestinal involvement with malabsorption syndrome and weight loss). These patients have a poor prognosis.

Mast cell leukemia

Mast cell leukemia is detected when there are 10% or more atypical mast cells (cells with multilobed or multiple nuclei) in the peripheral blood and 20% or more in the bone marrow. The prognosis is bad. The life expectancy of such patients is usually less than one year.

Mast cell sarcoma

Mast cell sarcoma is an extremely rare form of mastocytosis. To date, only isolated cases of this disease have been described in the world. This is a destructive sarcoma consisting of very atypical mast cells. In these cases, no systemic lesion was found at diagnosis. However, secondary generalization involving internal organs and hematopoietic tissue has been described. In the terminal stage, mast cell sarcoma may be indistinguishable from aggressive SM or mast cell leukemia. The prognosis for patients with mast cell sarcoma is poor.

Mast cell sarcoma should not be confused with extracutaneous mastocytomas, rare benign mast cell tumors without destructive growth.

Prevention of systemic complications of mastocytosis

Since systemic complications associated with the release of biologically active substances from mast cells are possible not only in patients with SM, but also in any skin form, with the exception of persistent macular eruptive telangiectasia (if it is not combined with SM), such patients should adhere to the following rules [8]:

- In the event of anaphylaxis, it is advisable to have two or more automatic syringes with epinephrine, especially if you plan to go outdoors (unfortunately, there are no such syringes in Russia).

- Patients with IgE-mediated allergies, if indicated, receive allergen-specific immunotherapy to reduce the risk of developing allergic reactions.

- You should avoid eating foods that can cause mast cell degranulation: seafood (squid, shrimp, lobster); cheese, alcohol, hot drinks, spicy foods.

- The following medications should be avoided if possible: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, especially Aspirin, as they promote direct degranulation of mast cells; antibiotics - vancomycin, polymyxin (including drops for external treatment), amphotericin B; dextran (Reopoliglucin solution for intravenous administration, as well as a component of eye drops for moisturizing the cornea); quinine (antiarrhythmic drug); narcotic analgesics (including codeine in cough tablets, morphine, etc.); vitamin B1 (thiamine); scopolamine (in eye drops to treat glaucoma). The use of certain drugs during anesthesia is undesirable. In particular, succinylcholine and cisatracurium have the least ability to degranulate mast cells; aminosteroids (vecuronium, rocuronium, rapacuronium) - moderate activity; Atracurium and mivacurium are the most active in this regard and therefore their use is not advisable in such patients. Inhalational anesthetics are safe for patients with mastocytosis. Among intravenous anesthetics, ketamine has little effect on mast cell membrane stability, and the use of propofol and thiopental should be avoided [9]. When performing local anesthesia, benzocaine and tetracaine should not be prescribed (lidocaine or bupivacaine can be used). It is undesirable to use intravenous radiopaque iodine-containing preparations and gallium preparations; reserpine; beta-adrenergic blockers (propranolol, metaprolol, etc.). If the use of the above drugs is unavoidable, the patient should at least be given antihistamines first to prevent unwanted side effects. If it is necessary to undergo surgery or an X-ray examination using iodine-containing radiopaque agents, corticosteroids are additionally administered (for example, prednisolone 1 mg/kg body weight - 12 hours before the procedure, followed by a gradual reduction in the dose over three to five days).

- You should pay attention to the composition of cosmetics and detergents, where methylparaben may be used as a preservative. This substance can also cause mast cell degranulation.

Treatment of mastocytosis

Cutaneous mastocytosis in children, if it is not accompanied by systemic symptoms, usually does not require treatment, since it tends to heal itself. Measures to prevent mast cell activation are important here. In case of systemic symptoms, antihistamines are the mainstay of therapy. Since skin symptoms (redness, itching, urticaria) are mediated primarily through H1 receptors, they can be controlled with antihistamines. H1 antagonists may also relieve gastrointestinal spasms. H2 receptor antagonists suppress excessive acid secretion in the stomach, which is an important factor in the development of gastritis and peptic ulcers. Although there is no specific evidence regarding which antihistamines provide significant benefits, combining H1 and H2 blockers appears to be more effective in inhibiting the effects of histamine. H2 antihistamines are often ineffective in controlling diarrhea. In this case, anticholinergic drugs or cromones may provide relief (Tables 4 and 5). Cromones prescribed orally, in addition, relieve skin symptoms, disorders of the central nervous system, and reduce abdominal pain.

Like cutaneous mastocytosis, indolent SM is treated with antihistamines.

Systemic corticosteroids may help with severe skin rashes, intestinal malabsorption, or ascites. Topical corticosteroids, especially as occlusive dressings for a limited period of time, or intralesional corticosteroid injections may temporarily reduce the number of mast cells and relieve symptoms. Such methods are used for mastocytomas in some cases. Photochemotherapy (ultraviolet irradiation of the spectrum A in combination with a photosensitizer, PUVA therapy) leads to a decrease in itching and the disappearance of rashes, but after cessation of therapy, symptoms resume. Leukotriene receptor inhibitors are used to relieve itching, but there is little data on the effectiveness of such therapy. Interferon alfa may control symptoms of aggressive SM, especially when combined with systemic corticosteroids. Interferon alpha is also used to treat osteoporosis caused by SM [7]. Relatively recently, a tyrsine kinase receptor inhibitor (Imatinib mesylate) has appeared, which can be used in aggressive SM, but in Russia this medicine is only allowed to be used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. If hematological diseases are present, patients should receive appropriate treatment.

Treatment for mast cell leukemia is similar to that for acute myeloid leukemia, but no effective treatment has yet been found.

Literature

- Valent P., Akin C., Escribano L. et al. Standards and standardization in mastocytosis: Consensus Statements on Diagnostics, Treatment Recommendations and Response Criteria // EJCI, 2007; 37:435–453.

- Skin and venereal diseases: A guide for doctors. In 4 volumes. T. 3. Ed. Yu. K. Skripkina. M.: Medicine, 1996. 117–127.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. Clinical Dermatology, 10th Edition // Saunders/Elsevier, 2006: 615–619.

- Bradding P. Human Mast Cell Cytokines // CEA, 1996; 26 (1): 13–19.

- Golkar L., Bernhard JD Biomedical Reference Collection: Comprehensive Seminar for Mastocytosis // Lancet, 1997; 349(9062):1379–1385.

- Handschin AE, Trentz OA, Hoerstrup SP et al. Effect of Low Molecular Weight Heparin (Dalteparin) and Fondaparinux (Arixtra®) on Human Osteoblasts in Vitro // BJS, 2005; 92: 177–183.

- Valent P., Akin C., Sperr WR et al. Mastocytosis: Pathology, Genetics, and Current Options for Therapy // Leukemia and Lymphoma. 2005, Jan; 46 (1): 35–48.

- Khaliulin Yu. G., Urbansky A. S. Modern approaches to the diagnosis and drug therapy of dermatoses (a textbook for the system of postgraduate and additional professional education of doctors). Kemerovo: KemGMA, 2011: 130–131.

- Ahmad N., Evans P., Lloyd-Thomas AR Anesthesia in Children with Mastocytosis - a Case Based Review // Pediatric Anesthesia. 2009; 19:97–107.

Yu. G. Khaliulin, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor

GBOU VPO KemSMA Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia, Kemerovo

Contact information about the author for correspondence

Diagnosis of mastocytosis and its treatment

Diagnosis of cutaneous mastocytosis includes a history and physical examination, and laboratory tests to see if there is damage to other organs.

Diagnosis of mastocytosis may include the following:

- physical examination for rashes, enlarged lymph nodes, enlarged liver and spleen;

- detailed clinical blood test;

- skin biopsy if necessary;

- It is possible to prescribe an abdominal ultrasound or CT scan.

As a rule, children with cutaneous mastocytosis have a favorable prognosis if it appears in the first 2 years of life, because spontaneous resolution of the disease occurs most often in this age group after several years, before puberty.

Manifestations on the skin begin to disappear after the child is 5-6 years old, the average duration of the disease is 10 years.

Mastocytomas can go away on their own after a few years.

If cutaneous mastocytosis develops after 2 years of age or older, as well as in adulthood, it usually persists. Despite this, in more than 80% of children with cutaneous mastocytosis, the disease resolves on its own.

The treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis is carried out by a pediatrician, if necessary, involving more specialized specialists: a dermatologist, hematologist, allergist and others.

Classification of mastocytosis

Medicine distinguishes four clinical forms of the disease:

- Cutaneous mastocytosis. It appears during the first years of the baby's life. Skin lesions that occur in a young child during illness almost completely disappear during puberty. There are no lesions of internal organs. The rarest case is the transition of cutaneous mastocytosis to systemic mastocytosis.

- Cutaneous mastocytosis in adults and adolescent children can affect not only the skin, but also internal organs, spreading the infiltration of mast cells to the kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, heart, liver, and mucous membranes. The changes that occur in the patient’s body do not progress further; this differs from systemic mastocytosis. In rare cases, cutaneous mastocytosis in adults can develop into a systemic form.

- Systemic mastocytosis. Its symptoms usually appear in adults. This is a progressive form of the disease that affects internal organs. There are known cases of effects on the skin.

- Malignant mastocytosis. Its causes are malignant degeneration of mast cells. It is this form of the disease that received the second name - “mast cell leukemia”. Degenerated mast cells infiltrate tissues and internal organs of a person, which leads to death. Skin lesions in malignant mastocytosis are usually absent.